- Home

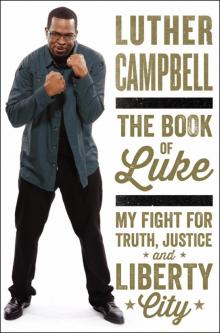

- Luther Campbell

The Book of Luke

The Book of Luke Read online

DEDICATION

To my family—my wife, Kristin; my sons Blake and Brooklyn; my daughter Lutheria; and my two adopted sons, Devonta Freeman and Durell Eskridge. To my father, Stanley Campbell; my mother, Yvonne Campbell; my uncle, Ricky Stirrup; and my Liberty City Optimist Family. And to two of my best friends, Nikki Kancey and Tresa Sanders, who have always been by my side, through the good times and the bad; through the ups and the downs.

EPIGRAPH

“So that you may know the exact truth.”

—THE BOOK OF LUKE 1:4

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

[Author’s Note]

I

Liberty City

Miami Beach

Ghetto Style

Riots

II

Luke Records

2 Live

All In

Move Somethin’

Handsome Harry

III

The Hurricanes

Nasty

Obscene

Rock Star

Still After Me

Bankrupt

Luther Campbell v. Uncle Luke

IV

Optimist

Coach Luke

Champions

Charles Hadley Park

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

[AUTHOR’S NOTE]

My father was a janitor. He worked at the same elementary school in Miami for twenty years. Before that he worked as a forklift operator at the Food Fair. It was a better job with better pay and better hours, but he was fired for insubordination, for being a black man who wasn’t afraid to stand up for himself. My father wouldn’t apologize to a manager who insisted that he’d done something wrong, something he didn’t do. My father could have kept his head down and kept his job, but he refused. He left and took a menial, lower-paying job someplace else because he wasn’t going to eat shit for anyone.

I am my father’s son, and this is my story . . .

I

LIBERTY CITY

I was born on Miami Beach, at Mount Sinai hospital, on December 22, 1960. How I came out, what time I came out, I don’t know. What I do know is that it was unusual for me to be born there. Miami was still segregated, same as the rest of America, and at the time black people weren’t even allowed on Miami Beach except to work as maids and janitors at the resorts. If you were a black person working on Miami Beach, you had to carry an ID card. Get caught without your card and you’d be escorted off the island or taken to jail.

The greatest black performers in America, going back to Count Basie and Duke Ellington and all the way up through Sam Cooke and James Brown, they’d play their gigs at the Fontainebleau and the Eden Roc, but then after the curtain went down they had to cross the bridge to stay at the Charles Hotel in Overtown, Miami’s original black neighborhood. It was the same for Muhammad Ali when he was training at Angelo Dundee’s 5th St. Gym for the heavyweight bout against Sonny Liston. He’d come down to train at the gym, then he’d have to catch a bus back to Overtown at night.

In 1960, black people who wanted to be born were supposed to go to Jackson, the city hospital. But not me. Later on down the road, whenever I had issues with my club, Luke’s Miami Beach, or when I got flack for trying to bring hip-hop concerts and conventions to Miami Beach, I’d always throw it in people’s faces. I’d say, “Motherfucker, I was born here. I was born on Miami Beach. This is my city.” It blows people’s minds.

I never asked how she came to give birth to me at Mount Sinai. I can only figure they had some interns from the university, and they were encouraging blacks to come over so they could run experiments on them. Maybe I was an experiment. It was a pretty telling way to start the life of Luther Campbell: not even five minutes in this world, and I was already making noise someplace I wasn’t supposed to be.

The history of black Miami is unique, different from any other major city in the South. There was no slavery here. Some landowners had tried to bring it down, before the Civil War, but the swampland was so brutal that for a long time every attempt to settle the area failed. The blacks who did come to south Florida were escaped slaves who’d fled from Georgia and Alabama to disappear into the Everglades with the Seminoles. Or they were Bahamians or other free Caribbean folk who came to fish and farm. White people didn’t know how to live and thrive in the tropics. Bahamians did. They knew the agricultural practices to use, how to fish, how to use lime mortar to build houses. There would be no Miami if blacks hadn’t built it.

When south Florida was a sleepy backwater, cut off from the rest of the state, it was an okay place for blacks to live. There was more equality. The black people here were fiercely independent, proud, hardworking, educated. We had our own thriving community and business district in what would become Coconut Grove. There was a high level of home ownership and civic engagement. When the city of Miami voted to incorporate in 1896, over 40 percent of the registered voters were black.

We were here from the beginning. This was our town. But then the railroads came. The railroads brought capitalism, and capitalism brought exploitation. Once Miami became a lucrative resort destination, all that black pride and independence was no match for the power of white money. White businessmen and real estate speculators poured into Miami and began buying it up and selling it off, piece by piece. Wealthy white tourists started coming. Miami needed blacks to dig the ditches and clean the hotels, but those blacks had to be kept out of sight and out of mind. Racial covenants and restrictive zoning started pushing us across the same railroad tracks that we’d built, into a neighborhood called Overtown. It got its name because it was on the other side of downtown from Coconut Grove, and you had to go “over town” to get there.

Miami began to take off, especially Miami Beach. It was the American Riviera, full of beautiful oceanfront mansions and art deco resorts. By comparison, Overtown was a slum, families living in wooden shacks with no city services and no sanitation. There were lots of houses without electricity or running water; people still used woodstoves and oil lamps. Despite how we were forced to live, the black community thrived in its own way. We built our own banks, our own hotels, our own restaurants and nightclubs. There were great movie houses: the Ritz and the Lyric and the Modern. Anything you could get in Harlem, you could get in Overtown. It was separate and segregated, but it was ours.

Second Avenue was the main drag. Friday and Saturday nights, men and women would step out in their finest to hear Hartley Toote’s house band at Rockland Palace, or Count Basie at Harlem Square Club. The big acts that came to town, like Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith, they’d play their gigs over on Miami Beach, get off around midnight, and then come back to the clubs in Overtown and play crazy, nonstop sets until the sun came up. There was dirt and disease right off the main drag, but out on the avenue, shit was jumping.

My mother grew up in Overtown, born and raised. Her father had come over years before from the Bahamas for work. She was Yvonne Galloway before she married my father, and she and her sisters were known as the most drop-dead-gorgeous women of Overtown, the Galloway girls. I don’t know how my old man got in there, but he did, and after they got married they lived together with the two boys from her first marriage in an apartment right in the heart of Overtown.

Then they started kicking us out.

Overtown sits right down by the water, about two blocks from where the Miami Heat arena is today. As the city grew around it, it became some of the most valuable property in the whole south of Florida. Developers wanted the land for more condos and office buildings and hotels. At the time, the federal government wa

s building the interstate highway system, and I-95 was going to be run straight down through the heart of Miami. Urban renewal, they were calling it. The original plan called for running the highway over the old Florida East Coast railroad tracks, which was already a transit corridor and would have caused little disruption. But the plan was deliberately shifted west to run through the heart of Overtown.

The community was destroyed, intentionally, to make way for white developers. Overtown’s business district was gutted. They razed whole city blocks and started moving families out. The houses that weren’t destroyed, the city went through and started evicting people. After years of forcing blacks to live in substandard housing, the city sent out inspectors and if they found any code violations (which they always did), they’d use it to evict us. In the years that followed, the population of Overtown dropped from forty thousand to ten thousand. Some people stayed, but the heart and soul of the community was being ripped out, and a lot of families moved away, including mine.

The other part of clearing us out was building someplace for us to go. Back in the 1930s, there was a white neighborhood just north of Overtown called Liberty City. Responding to the overcrowding conditions in Overtown, in 1937 the federal government had gone into Liberty City and built the Liberty Square Houses—it was only the second public housing project in the country and the first in the South. The white families in Liberty City were so panicked about all these poor blacks moving in that the city actually built a wall that ran down the middle of Twelfth Avenue, from Sixty-Second Street to Seventy-First Street, to separate the new projects from the white parts of town.

Liberty Square had modern kitchens, electricity, hot water, all these conveniences that were going to entice black families to move out of Overtown. The projects were very different than when I was growing up. By the time I was a kid, they were already falling apart. Same as with Overtown, they weren’t maintained. There was no investment from the city to keep them nice. Eventually nobody called it Liberty Square anymore. Everyone called it the Pork N’ Beans, because that’s all the people who lived there could afford to eat.

Some black families moved out to take advantage of the new homes, but most black families wanted to stay in Overtown. Then the interstate came and black families started pouring out, spreading north into Brownsville and Caledonia and Carver Village. Sometimes the families moving in were met with protests, sometimes with dynamite. They kept coming because there was nowhere else for them to go.

My parents left Overtown when the interstate was built, moving first to an apartment in the Caledonia neighborhood. My father started looking for a house to buy with some of the money he and my mother had managed to save. He saw an ad in the paper for nice houses over in what was still the white part of Liberty City; my father being my father, he didn’t care where the color line was. He was going to put a roof over his family’s head.

These homes were being advertised for just $500 down, but when my dad showed up and the real-estate agent found out he was black, suddenly the down payment jumped to $2,500. He must have figured my father didn’t have it, or maybe he was just trying to fleece us for as much money as he could get. My parents had to borrow a little here and there, but they came up with the down payment. Two years before I was born they moved into this little house at Eleventh Avenue and Fifty-Eighth Street. Within a few years, the whole area had flipped all-black.

When my father closed on the house, he read in the property deed that it could only be sold to whites. There are still people pulling that crap around here today. They just use code words for it now.

When I was really little, Overtown was still a fun place to visit. We used to go to the movies there at the old movie houses. On weekends, me and my brothers would go and stay by our granddaddy’s house, stay by our uncle’s house. We’d go there for holidays. But as the years passed, it was less and less. For half a century, Overtown had been the heart and soul of black Miami, but those days were over. The older I got, the more we identified with Liberty City. “We City,” we’d say. That is the heart of black Miami now.

When I was growing up, our house was no bullshit. Island people are work, work, work. Everything was always about business and education and getting ahead. My father, Stanley Campbell, emigrated to the United States as a young man to look for work. He was Jamaican, a proud Jamaican. To this day, if you sat down next to him and called him an African-American, he’d say, “African-American? I’m Jamaican.” Then he’d give you the whole history of the island, the people, the political struggles against the British, all of it.

My father worked as a custodian at Highland Oaks Elementary, and he co-owned a barbecue joint in the neighborhood with his friends. He worked the restaurant on the weekends and, during the week, worked the night shift at the school. He would always take me and my brothers to work with him and pay us to do odd jobs, help him out. He worked throughout the year, and in the summertime or anytime we had an off week, we would go over there and work with him; even if the kids have a week off, the janitors were still working. So instead of us sitting home, we would go with him. He never gave us an allowance. The only way we could get money was if we worked for it. “In the real world, money is at the end of a day’s work,” he’d always say. He and my mother opened us all bank accounts and made us save half of everything we earned. He was constantly teaching us about the need to have a good work ethic and make it on our own. He was always telling us to have self-respect and a sense of self-worth. He demanded that we be men and learn responsibility.

Everything my father did, he would think seriously about before doing it. He’d deliberate over all his options, then make a decision about what path to take. Once it was done, he’d stand by it. He’d never change his mind no matter what. His one quirk was that he could never say he was sorry, not for anything. Some people are willing to apologize even when they haven’t done anything wrong, just to keep the peace. Not my father. He’d say, “Don’t ever say you’re sorry for something you didn’t do just to keep other people happy.” If you’re going to do something, then stand by it. If he realized he’d been wrong, he’d change his behavior and do right going forward, but he’d never go back and apologize for the original decision.

I’m exactly the same way. I’m like my father in so many ways. I learned a lot from him. Unsurprisingly, we always butted heads. We didn’t like anything that the other one liked. If he liked the Miami Dolphins, I liked the Dallas Cowboys. I loved and respected him, but we continually had beef with each other. My brothers used to call me a mamma’s boy. My mother and I were so close. I called her “my old gal.” I was the youngest, her baby, and she’d take me everywhere to do everything with her. I was her favorite, and she’d tell as much to anybody who asked. She was slow to punish me even when I probably deserved it. If I had a fight with my brothers or my dad, I’d go and hop in the car with her and ride off into the sunset.

My mom was every bit as tough as my dad, had that same island work ethic. She was a beautician, famous in the neighborhood. Her beauty salon was called Beautyrama, at Fifteenth and Sixty-Ninth Street. My godmother owned the place. I used to hang out around there a whole lot. My mother did hair standing on her feet all day, even when she got sick, and she was always getting sick. She had rheumatoid arthritis and her hands got worse and worse over the years but she never stopped working. Later on she got cancer and she worked through the cancer, too. I never once heard her complain. She gave me and my brothers chores around the house from the time we could handle them. She never wanted us to be unable to take care of ourselves. She taught us all how to cook, clean the kitchen, clean the bathroom. I know some guys can’t even make a pot of rice without a woman there to do it for them. Thanks to my mom, I’ve always been able to handle things on my own.

Even though she was as tough as my dad, she had a softer side. Where my dad was macho and prideful, my mom was understanding and trusting. She always had a hug for you and was always laughing. We were poor, but we never knew

it growing up. We never went hungry, not even for a day. My mother made sure there was always a hot meal on the table for breakfast and a snack waiting for us after school. She fed the whole neighborhood. She always had a big pot of something going on the stove, and the door to our house was always open. If our friends came over to play and made the mistake of looking skinny or hungry around her, she’d feed them on up to full. If anybody came over smelling bad, she’d give them some soap and say, “Take your ass in there and take a bath.”

Both my parents had a strong influence on me. Island people are a very family-oriented people. Everybody gets drunk on Friday, cusses each other out on Saturday, and gets back together for boiled fish and grits on Sunday. What’s funny is that I remember them having this powerful presence in my youth, but the reality was that they weren’t around all that much. My father worked the night shift, and being a beautician sometimes had my old gal working day and night. Their personalities were just that strong; the time I did get to spend with them left a huge impression. Day to day, I was mostly raised by my brothers. Our parents laid down the law, taught us good values, and expected us to take care of ourselves.

I was the youngest of five brothers, and we lived in this tiny house. It was two bedrooms and one bathroom, with all five of us boys living in one eight-by-ten room. I slept on the sofa most nights, just because I preferred to be on my own. The two oldest, Steven and Harry, were from my mother’s first marriage to a man named Newbold. They were a lot older than the rest of us. When Steven left for Vietnam I was still in diapers. The three youngest were Stanley, Brannard, and me.

Everybody in the family had some sense. All of my brothers went to college. Steven did two tours in Vietnam so Harry wouldn’t have to go; he knew if he reenlisted they wouldn’t put two brothers in the same combat theater. Steven came home with a 95 percent disability rating because of the damage the Agent Orange did to his lungs. He became a clinical psychologist working with combat vets who have PTSD. Harry got a degree in chemical engineering and went to work for Monsanto—the company that made the Agent Orange. Brannard became an executive chef.

The Book of Luke

The Book of Luke